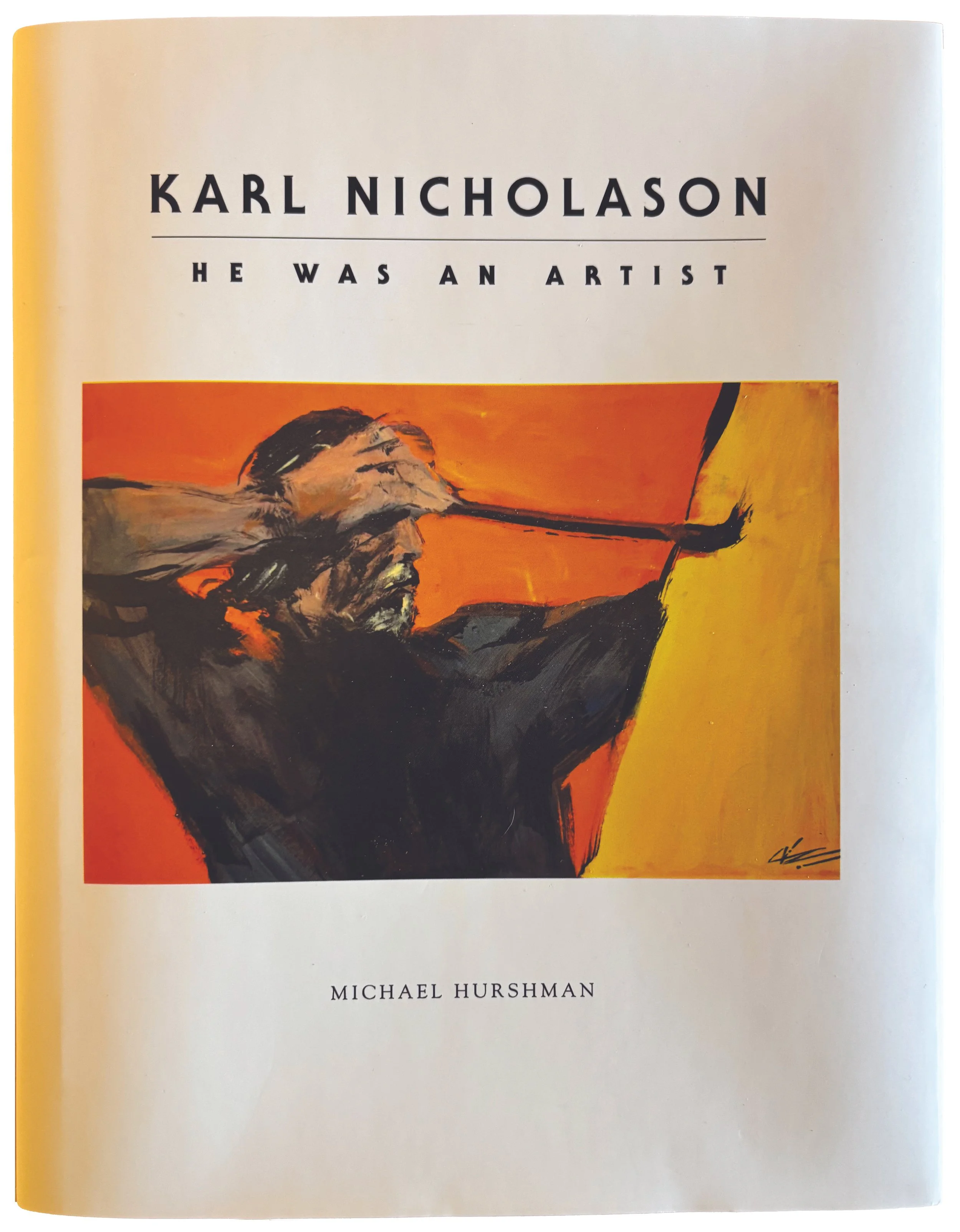

He Was An Artist: Karl Nicholason’s Creative Legacy

Karl Nicholason epitomized the stereotypical tortured, starving, genius artist — and yet his story and creative works are anything but cliché. A new book, titled Karl Nicholason: He Was An Artist, outlines his life and presents unpublished works.

Before Nicholason died in 2022 at age 82 in Grand Junction, he survived both the heights and the horrors of an artist completely dedicated to his own vision.

In the 1960s and ’70s, he lived in Southern California, working as a principal illustrator for Psychology Today. He became a well-respected commercial illustrator for psychology, science and sociology textbooks, and created images for magazines ranging from Saturday Review to Playboy.

“His imagination, coupled with exceptional technical skill, were well-suited for the psychedelic era of counter-culture self-exploration promoted by Psychology Today,” author Michael Hurshman points out in the book, later adding: “His technical proficiency as a draftsman coupled with his ability to visualize a client’s concept in a colorful and captivating psychological diorama was unique for the time and became his professional calling card.”

Biology Today, a college textbook, was produced by the publishers of Psychology Today. Their offices were in Del Mar, California. Kitty worked there in the ‘70s. Courtesy of Michael Hurshman.

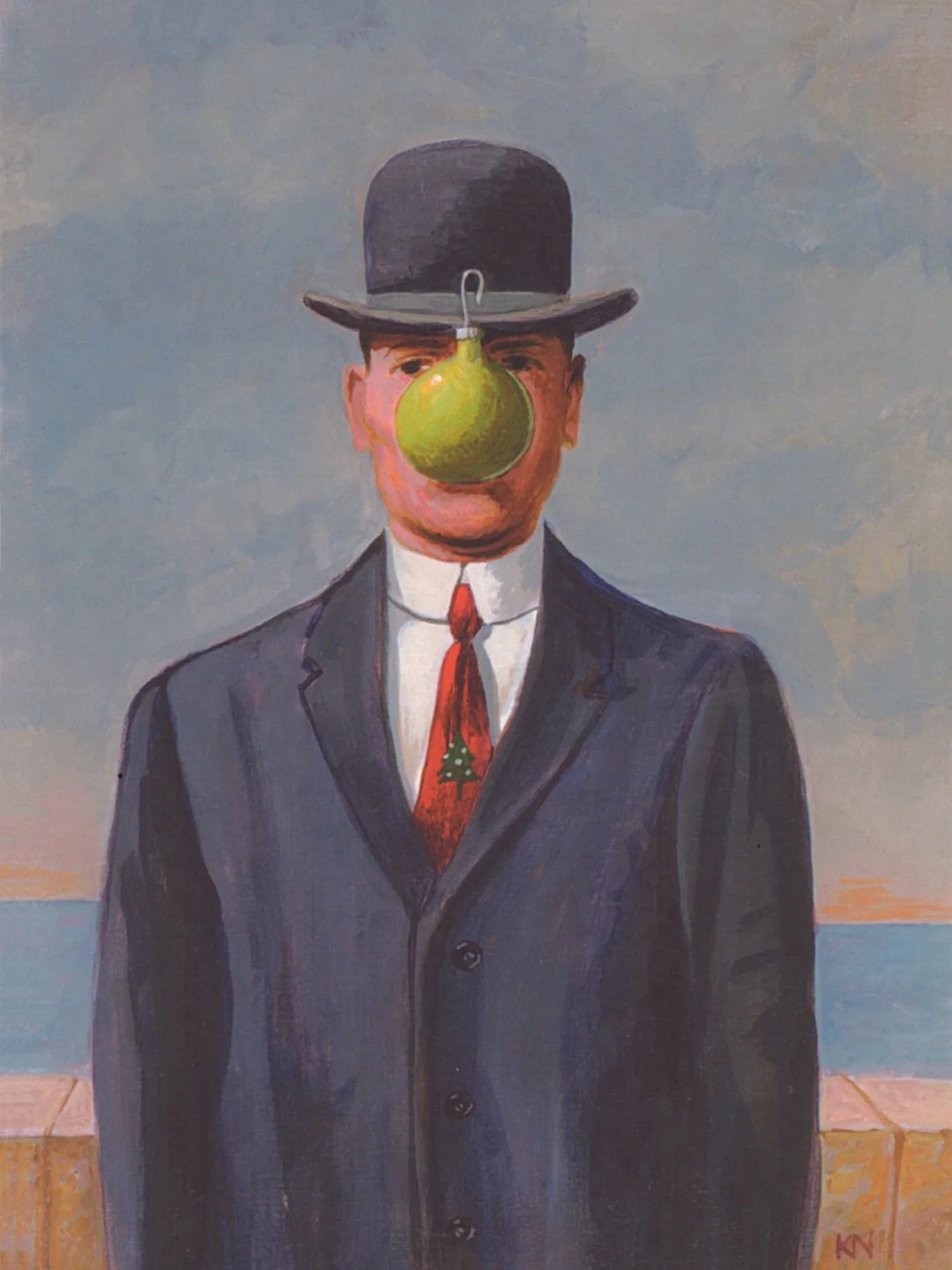

A client with a new greeting card company found Pyramid Printing, where Kitty worked, and said she needed an illustrator. Karl was a perfect fit for the job — and the client — and he worked happily and profitably for quite a while. This is a Christmas card featuring a play on a Magritte painting.

But by the 1980s, commercial tastes had changed, and Nicholason had no interest in catering to them — or to galleries. He respected only a handful of masters, viewing the rest as “hacks,” a label he certainly didn’t apply to himself. His thumbnail sketches, many of which the book showcases, demonstrate his skill in perspective, line, medium and subject, regardless of scale. Some of his effects still baffle artists. He also relied on his photographic memory rather than reference material.

Despite the fact that his vast — and surprisingly self-taught — techniques would have allowed him to produce just about anything, he refused to meet market demands that didn’t suit him.

“He wanted to do what he was motivated to do. He just thought people should recognize his brilliance and reward him for it — and, I mean, he was brilliant,” Hurshman says.

Karl did not like people asking him: ‘What does this mean, or why did you do that?’ He’d get real irritated, partly because he probably didn’t even know, and it bugged him to have to try to analyze his art because he didn’t do it to have to analyze it.

Karl produced illustrations in a wide range of styles. In fact, his nickname in San Diego was “Dial-A-Style.”

He notes in the book: “His art is deeply personal and involving his complex psychology and life experience, rooted in a singular obsession with expressing his inner turmoil and vision. He was his own audience. His art, outside of the contracted commercial obligations and infrequent gallery representation, was never created for public consumption. The decorative art market was of particular disgust to him.”

His frustrations around conformity ultimately spiraled into depression, overreliance on alcohol, divorce and homelessness. Still, he continued to constantly create, sometimes drawing on toilet paper rolls because he couldn’t afford supplies. He stated in one sketchbook: “If I don’t paint to empty my mind, I’ll go mad.”

Karl and Barney in his studio on Jimmy Durante Blvd. in Del Mar, California, October 1983

His initial success, artistic talent and “fun life” attracted Kitty Nicholason, and they married in 1983. Granted, she wanted to “domesticate” him, teaching him financial responsibility and marketability, but he didn’t — or couldn’t — grasp either. Growing more despondent in California, he began to talk about Colorado. He had been stationed in Denver from 1957 to 1961 after enlisting in the Air Force at age 17, where his photographic memory resulted in extraordinary Morse code communication. Upon discharge, he briefly studied at The Art Institute of Colorado before rebelling against academics.

After carving a life near the Del Mar beach they so loved, the couple settled into an affordable dream home in Grand Junction, where properties were financially attainable, as opposed to California.

“We moved in 1990, and it was great at first,” Kitty Nicholason says.

But Western Slope clients didn’t pay what he was accustomed to. One client with homes in Laguna Beach and Durango hired him for a fair amount of illustration work, but he broke off the relationship over a perceived slight, she says.

“Karl never wanted to go out and hustle work. He always assumed he would just be discovered — he was that good … I absolutely fell in love with his artistic ability, but I wanted to have a normal family life, and he was just too prickly, and he never missed an opportunity to tell me I was doing something wrong,” she says, adding that alcohol and lack of money increased the pressure. “He was fine on beer, but if he had tequila, oh my god. He was never physically violent with me or our son, but I spent the last four or five years walking on eggshells trying to make sure that he was happy so that I could be happy.”

In 1998, after 15 years of marriage, they divorced. Once she remarried, he no longer affected her moods — so much so that she moved a hospital bed into her home when he fell ill before his death. “He mellowed a bit in the end,” she says.

Still, that didn’t prevent his son — whom he references in drawings about not having enough money to buy a gift for during his homeless days in Denver — from estranging him several years before his death.

“He was remarkably good at one thing and was unable to do almost anything else,” Hurshman says. “He did not function well in society. He was introverted, typically poor, and he just sat in his little room probably drinking too much beer and tequila at times and drawing and painting. That was his life.”

Hurshman, an art collector, met him in Grand Junction in the mid-1990s but lost touch while he was homeless for more than two years in Denver in the early 2000s, during a period when he was finally seeking gallery representation. Sketches in the book viscerally speak to Nicholason’s isolation, poverty, desperation and hopelessness.

The 200-page book designed by Kitty Nicholason and published by Michael Hurshman in 2025.

“I viewed his act of making art as somewhat of an exorcism,” Hurshman says. “He had demons, and that’s how he got them out. He was very unemotional about his art; when he was done with the piece, he was done with it. He didn’t go back and edit and agonize. When he got it out of his head, he just did another one and another one and another one until he was exhausted or passed out.”

Not wanting Nicholason to remain unrecognized after his death, Hurshman spent more than two years sorting through the nearly 3,000 drawings and paintings stuffed haphazardly in the artist’s tiny Grand Junction dwelling. With an aim to “make order out of the chaos that was Nicholason’s world,” he structured the book into seven categories: vignettes ranging from satirical relationships to domestic violence; social commentary, often including Nicholason’s sarcastic wit; alienation; works inspired by the masters; land- and seascapes; the La Infanta Margarita series inspired by Velazquez’s 1659 paintings; and other works.

Most do not include explanations. Rather, cryptic and often disturbing illustrations, which include references to mythology, clever word play and repeating symbols such as starfish, are left to the viewer’s imagination.

“It is quite possible that even Nicholason would be unable to coherently describe his motivation for the subject,” Hurshman writes. “He once told me that he would commonly wake up after a night of heavy drinking, and paintings or drawings would be on his drawing table. He had no reference materials other than his inner torment and no memory of creating the images.”

“I learned not to ask a lot of questions,” he says. “He did not like people asking him: ‘What does this mean, or why did you do that?’ He’d get real irritated, partly because he probably didn’t even know, and it bugged him to have to try to analyze his art because he didn’t do it to have to analyze it. He did it to get it out of his head.”

Yet, he obsessed over color mixing and typically documented his experimentations.

A book designer by trade, Kitty Nicholason designed the book using her ex-husband’s favorite typefaces. Hurshman says the overall quality of the artist’s works were so high, he could’ve compiled the book with totally different images and been equally as happy with it.

“I have a couple of friends who were big-time illustrators in their day, and they looked at the collection and went, ‘Oh my god, I’ve never seen anything like this. Who is this guy?,’” he says.

Apart from his early illustration awards, only this book and two major paintings in the permanent collection of The Art Center of Western Colorado in Grand Junction honor his talent. However, after seeing the book, The Leonardo — a major museum in Salt Lake City — offered to dedicate 2,500 square feet to exhibit Nicholason’s work for two months last summer. Unfortunately, financial issues forced the museum to cancel the show. As of press time, the museum hoped to highlight his art in the fall.

“He should’ve been discovered,” Kitty Nicholason says. “Maybe a different personality would’ve dominated. But his talent. He’s right up there — I think — with the big kids. I really do.”

Originally published in the fall 2025 issue of Spoke+Blossom.